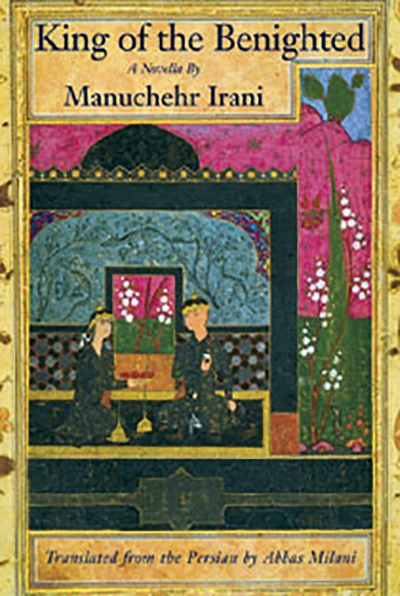

King of the Benighted was mailed out of Iran page by page. It is both a firsthand account of the hard realities of life under the Islamic Republic and a literary masterpeice by one of Iran’s best contemporary writers, Houshang Golshiri, who wrote under the pen name Manuchehr Golshiri to protect his identity. Golshiri has creatively combined modern techniques of fiction with the rich tradition of Persian poetry to tell a timeless tale. The novella invites the reader to join the flow of the artist’s imagination and to share moments in the life of a contemporary Iranian poet, including his imprisonment and incredible encounter with a young prisoner called Sarmad. Should you want to know why Iran has become a nation of mourners, you might follow the poet where he has gone.

King of the Benighted epitomizes a new emerging spirit in contemporary Persian literature and shows that despite Iran’s isolation today, its literature is very much part of the spirit sweeping the world. Included in this volume is an English prose rendition of the central metaphor of the novella, the 12th century poet Nizami’s “The Black Dome.” An insightful introduction by Nasrin Rahimieh and a perceptive afterword by the traslator reflect on the state of post-revolutionary Persian literature.

Note: This book was originally published in a numbered clothbound limited edition of 975 copies.

The German language edition is available from Amazon.de (Amazon.com’s German branch).

[/tabber]

[tabber]

Excerpt

Introduction to King of the Benighted

by Nasrin Rahimieh

At a time when the world has just celebrated the end of a decade marked with momentous change, it would seem inappropriate to speak of The Demonic Decade–the title the poet protagonist of King of the Benighted has bestowed upon a collection of his own poems. But his perspective is that of an Iranian who witnessed the brutal end of another era in 1979.

If we expect “The Demonic Decade” to set the tone of this novella, we are in for a surprise. King of the Benighted is not a litany of shattered ideals; it is a startling and at times ironic self-examination which never loses sight of the absurd and the humorous.

Led away to interrogation, the hero is grateful for small mercies: “So long as they hit with a book and on his head, then there is something to rejoice for.” Political commitment has given way to personal obsession. Will all of his books fit into the few boxes the interrogators have brought? Will they take away his precious copy of Nizami’s thirteenth-century poem? Will the cracked wing of the plaster angel, standing in his garden, survive the winter?

Those seeking the definitive symbolic meaning of every utterance made by the anonymous narrator will have their expectations thwarted at every turn. Like the thirteenth-century poem on which King of the Benighted is superimposed, this novella works on many levels. The poet’s remarks about Nizami’s The Black Dome are an apt description of the way in which his own novella should be read: “Well, that was the story. That is what he read. What counts is the interpretation. It has to be an inner experience, everyone must go through it.”

The “inner” journey upon which readers are required to embark is not unlike the one the king undertakes in The Black Dome. He sets out to learn why everyone is dressed in black in the City of the Bedazzled. He discovers the secret, only to emerge in mourning.

Should you want to know why Iran has become a nation of mourners, you might follow the poet where he has gone. Like the king in Nizami’s poem, you yourself may become ebonyclad. But, like the poet of King of the Benighted, while donning the obligatory black of the land, you might escape the worst and emerge with a head of white hair. In the end, you will be at once benighted and bedazzled.

All along the journey, illusions are shed and resolutions made. The wisdom at which the poet arrives while in prison is that he has indeed missed out on a decade. As he says to his cellmate: “I’ve been cheated. For about ten years, my only audience has been people like you. Now, I realize I haven’t written anything for a man in his forties, or even for myself.”

With this deaeration, the poet catapults his generation into a new literary era–one marked by an abrupt break with The Demonic Decade. He sees no point in writing about death, denouncing regimes, and spurring others to political action. For the anonymous hero of King of the Benighted, this is no time to lament, but a new chance at regeneration. This Iranian poet is, in spite of the isolation he suffers, very much part of the new spirit sweeping the world.

King also had to travel to China to find the City of the Bedazzled.