The Duke of Wellington observed, “Persia has been much exposed to authors.” During the nine years since the Iranian revolution, over one hundred new books on Iran have been published in English alone and there are hundreds more in French, Iranian, and other languages. Not all of them are reliable. Persia, or Iran, arouses passions. Not quite as Vietnam did, but for a much longer period. For students of Iranian affairs Dr. Ghani’s long book is, and will be, invaluable.

Before the fall of the Shah, Cyrus Ghani was a well-known Tehran lawyer, bibliophile, and connoisseur of movies. He was not part of the court but he knew everyone in the Pahlavi entourage. He was also a contact of the US Embassy, and a profile of him was found and later published, among many thousands of documents, by the militants who occupied the embassy in November 1979. (These documents, one of the most important collections of confidential US government papers ever to be made public, are available in more than fifty volumes. Some of them were shredded by embassy staff before the takeover of the mission was complete and have been painstakingly reconstituted, shred by shred.)

It was the habit of embassy officials, as in other capitals, to leave their successors lists of the best and worst contacts they had in Tehran. Some of the profiles found in the embassy are highly damaging to their subjects, who tend to be described as bores, sycophants, or crooks. Cyrus Ghani comes out well. Martin Herz, an astute US political counselor during the late Sixties, describes him as a most useful contact and good friend, but not without his blind spots:

He is “pro-American” in the sense that he shares our values and has a deep and truly encyclopaedic knowledge and interest In the US. But he is also a liberal nationalist and would not mind seeing the US humbled, not just in Iran but also in the Middle East. Cyrus Is a true conversationalist In the best sense of the word, and has a vast storehouse of knowledge about Iran. He is also a kind of intelligence exchange-he always seeks inside information and undoubtedly passes it along, so he cannot really be trusted beyond a certain point. On the other hand, he quickly tires of people who “just give me the line.”

If this comment seems unexceptional, compare it with what Herz wrote of Jamshid Kabir, against whose name he considered it necessary to issue a “WARNING NOTICE”:

Useless to try to discuss serious subjects with Jamshid, who is a courtier first and last. His wife, Marina, is a caricature. Great party goers, but it has never been clear why anyone would want to cultivate them. Their famous party in 1967 was distinguished by the fact that half the guests came down with acute poisoning, apparently because a devout Moslem on their household staff disapproved of merrymaking on a mourning day. Too bad Mrs. Kabir seems to have escaped unscathed.

I recall meeting Dr. Ghani In a beach house on Long Island In the fall of 1978; it was quite clear that he knew a revolution was coming to Iran. And so he had arranged for most of his library to be shipped out of Tehran to London and New York. Even so, he lost some 2,500 books. His Iran and the West, an alphabetically arranged critical bibliography of published works on Iran, is based on the many books, journals, and articles that are left.

It is therefore a somewhat eclectic work; it cannot and does not pretend to be exhaustive. It is nonetheless fairly comprehensive. Its sections-and Ghani’s library-embrace history, politics, and travel; literature, religion, science, language, and “Western Fiction with an Eastern Setting”; arts, archaeology, books of illustrations, photograph albums, and art-sale catalogs; pamphlets, articles, journals, occasional papers, museum catalogs, newspaper and news magazine articles.

That is a lot of subjects to cover, and although some subjects are merely mentioned, Ghani uses many of his entries as occasions to expound, and digress on, the turbulent history of Iran’s relations with the countries to its west. One reviewer has described the book as “a very high quality junk shop:’ This Is true insofar as it is much less predictable than an ordinary bibliography. It is the sum of Ghani’s prejudices, passions, and learning. He seems to know everything about Iran-and to have strong views on most questions. His book, like a good junk shop, is a wonderful place to browse in and linger.

He is particularly informative about the tortured relations between Britain and Iran in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Many Iranians believe, with some good reason, that Britain sacrificed the interests of Iran to its overwhelming concern to protect India, to which Iran was considered entirely sUbsidiary. Today Iranians are still obsessed with the British role in the continuing melodrama of their country. There are many who consider Khomeinl a British agent. There is a well-known saying in Iran, “Lift a mullah’s beard and you’ll see ‘Made in Britain’ on his chino” It Is commonly believed, particularly by those around the late Shah, that the British inspired the Shah’s overthrow and the Ayatollah’s return. Why? First to humiliate the United States, which had arrogated far too much (previously British) influence to itself during the time of the Shah. The British like shahs to be British not American puppets. Secondly, to create a crisis in the Middle East and thus inflate the price of North Sea oil, which was coming on stream in 1979. The Shah’s fall certainly had that effect, although no one has supplied any evidence of a British conspiracy to bring It about.

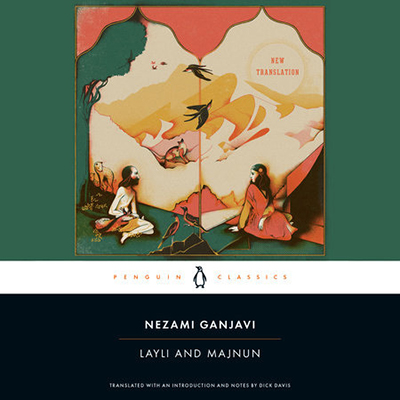

Ghani has more than forty pages on the various editions of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, which, while far from the most important Persian poem in Persia, is easily the most Important to foreigners. (That was a fact recognized by the Shah’s regime and among the scores of sumptuous illustrated books the court produced were many lavish editions of the Rubaiyat carefully designed to appeal to Western romanticism.) The Rubaiyat magnificent translation by Edward Fitzgerald was first published in 1859. It came to the attention of a number of writers, including Richard Burton, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and John Ruskin, who praised it very highly. It led Tennyson to become Interested in Persian poetry, and he considered translating Hafez. But Ghani tells us that his wife thought that the funny writing was harmful to his eyes, particularly when she learned that it had to be read backward. So she hid all his Persian texts and made him take up badminton instead.

Ghani’s prejudices are splendidly evident throughout. One book, An American Family In Persia, is dismissed as a “commonplace and useless work:” He describes the memoirs of the Shah’s second wife, Soraya, as “the best autobiography ever written by any half-German, half-Persian former Queen who later became an actress and made one film:’ Poor Soraya. Life at the Shah’s court in the Fifties does sound dismal. She hated the palace built by the Shah’s father, she hated the food, she hated traveling to the remoter provinces of Iran, and she hated the Shah’s scheming family. Above all, she hated Mohammad Mossadeq, “an aged tribal prince who was elected to parliament in 1950” and who seemed set on ruining her life. After the coup of 1953 in which she and the Shah first fled to Rome and then were restored with British and American help, things improved—until the Shah divorced her in 1958 for her failure to bear him children.

In discussing one of the Shah’s own memoirs, Mission For My Country(1961), Ghani draws on his own knowledge of court life in the Sixties and Seventies to give a portrait of the Shah that is both critical and sympathetic. Those who knew him as a young man often remarked on his “kindness”; he was also nervous and unconfident, while at the same time believing in his own divine mission. After the British removed his father and installed him as shah in 1941,

He was popular and had genuine support in almost all strata of Persian society. At his own initiative, he established a weekly informal meeting with some six or seven of the foremost scholars of the day where, In effect, he was to be educated…He was moved by poetry, amazed at tales of misrule by former monarchs, and saddened by Incidents of cruelty in Persian history.

Before the uprising by Mossadeq in 1953 the wise men were all very impressed by their young king.

Ghani believes the CIA-MI6 coup, which overthrew Mossadeq and restored the Shah to the throne, transformed him. From then on he demanded absolute and unquestioning support from a claque of “people of often dubious character and reputation:’ Still, there were “golden years” in the Sixties when the reforms, encouraged by Kennedy and called by the Shah his “White Revolution,” began to improve the conditions of Iranians.

Then came the election of Richard Nixon, whom the Shah knew and liked, the Anglo-American decision to make the Shah “policeman of the Gulf’ after the British withdrew from “east of Suez,” and Nixon and Kissinger’s “fateful” decision In May 1972 to give the Shah all the arms he wanted. At the end of 1972,

there was a marked change in the Shah. He grew more aloof and became more imperial and imperious. His arrogant treatment of his ministers became intolerable. The tone of his “talks” to the people became more remote…Corruption increased. Nothing could be done without the help of a contact in high places.

After the huge oil price rises of 1973-1974,

Some five or six super agents (together with some 25-30 sub agents) began to manage the economy…One of the key ministers devoted his entire time and energy towards fulfilling the wishes and financial interests of the Royal Family…There was a growing sense of injustice among the people and especially among the emerging middle classes. Violence and armed insurrection increased and was met by increased brutality and savagery. Large numbers of the young turned towards Islam for an answer.

In 1976 came the election of Jimmy Carter and the Shah’s decision to liberalize the regime—to try to transform himself into an Eastern Juan Carlos. Catastrophe followed.

Ghani notes that it is still hard to arrive at a just appraisal of the Shah. Iranians initially viewed him

as a tyrant, then as a saint, and now as a weak, vacillating nonentity who was a mere toy in the hands of others. He cannot be dismissed or ignored In these simple terms. The Iran of the last forty odd years, and in many ways the Iran of today, is his legacy.

Still, it is now nine years since the Shah departed. Nine years of the Ayatollah’s rule have also left ineradicable marks upon Iranian society. Ghani is an Iranian patriot who does not wish to see an Iraqi victory in the interminable brutal war of the Gulf. Yet his dislike for the methods of the revolution is abundant and clear. He writes disparagingly of a collection of lectures by Abol Hasan Bani-Sadr, the first president of the Islamic Republic. He calls his attempt

to identify Islam with the interests of the working class…a mixture of Marxism and Shi’ite fundamentalism in turgid prose and often Incomprehensible. Author…considered himself the “spiritual son” of Khomeini. He had the good fortune of escaping Iran before the wrath of his spiritual father had descended upon him.

Of another collection of essays, Iran Erupts (1978), edited by Ali Reza Nobari, Ghani is equally scathing. Among the contributors were Banl-Sadr, the French journalist Eric Rouleau, and Khomeini himself. The book’s self-proclaimed purpose was “to try to demystify the treatment of the anti-Shah movement In the Western media:’ Ghani writes that

the editor later became president of the Central Bank of Iran and was one of the principal financial geniuses behind Bani-Sadr who gave Iran the early Islamic-Marxist laws which probably are the most unworkable ever devised. The author and Bani-Sadr later fled their Islamic haven; M. Rouleau has since been appointed as French ambassador to Tunisia, and Ayatollah Khomeini has created exactly the kind of state which the present author accuses the Western media of Inventing.