Obstacles, prohibitions, uncertainties — these are essential to the blossoming and continuance of romantic love. They ensure that the imagination, rather than harsh experience, governs the erotic relationship: Unable to meet freely, the two lovers construct idealized versions of each other, to which they then offer their sighs, tears and hopes for happiness. Little wonder, then, that our most intensely romantic stories are largely about yearning rather than fulfillment: Think of Tristan and Isolde, Lancelot and Guinevere, Romeo and Juliet, Gatsby and Daisy, Leo Vincey and Ayesha (from H. Rider Haggard’s “She”).

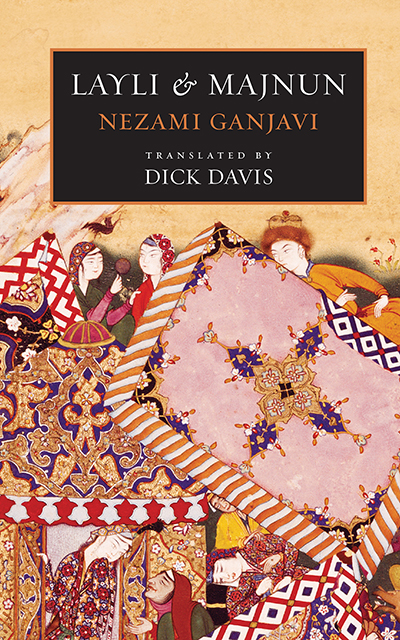

To that list one should add the protagonists of two of medieval Persia’s greatest romantic epics, “Layla and Majnun” and “Khosrow and Shirin,” both by the poet Nezami Ganjavi (1141-1209). In the first, the lovers experience suffering and madness before transcending the bodily to achieve a spiritual union reminiscent of the Liebestod (“love-death”) in Wagner’s opera “Tristan und Isolde.” Famous all over the Middle East, “Layla and Majnun” has also enjoyed some currency in English: I first encountered it in a simplified 1915 abridgment gorgeously illustrated by Edmund Dulac. In 2020, this arch-romantic work was freshly translated by the poet Dick Davis, and this is now the version to read. After all, Davis firmly established himself as our leading translator from Persian with his stunning 2006 rendering of the “Shahnameh,” a sprawling historical epic analogous in importance and influence to Homer’s “Iliad.”

This year, and just in time for Valentine’s Day, Davis and his publisher, Mage (located here in Washington), have brought out Nezami’s other great romance, “Khosrow & Shirin,” which draws in part on episodes from the “Shahnameh.” Once again, Davis emulates the original’s rhyming couplets, this time to tell the story of the last great pre-Islamic king, Khosrow Parviz, and his passion for the beautiful but strong-minded, almost proto-feminist Shirin (pronounced shih-REEN). It’s a fascinating work that challenges and rewards the modern reader in equal measure.

First, by today’s narrative standards, Nezami’s style is slow-moving, baroque and flowery. Italo Calvino once compared its richness to the glorious excess of Shakespeare’s “Venus and Adonis.” While Davis’s English always remains clear, Nezami revels in litanies of similes and metaphors, many requiring interpretation. Almond blossoms, for example, represent pale cheeks; breasts are likened to pomegranates (very “Song of Songs”); and a handsome maiden is regularly compared to a cypress tree. Invaluable endnotes clarify the more obscure meanings.

Still, Nezami’s expressions, in Davis’s English, can be striking on their own, as in this playful description of nightfall: “Beneath night’s ebony backgammon board/ The shining dice of day were safely stored.” In the exquisiteness of his singing, Khosrow’s court musician “could compete with tipsy nightingales.” As for Shirin, she possesses “eyes like life’s dark water,” while “each finger is as slender as a pen/ That signs death warrants for a hundred men.” One lavish section about Shirin’s physical beauty and the pleasures it will someday afford a lover could be summed up in the self-description of Flaubert’s Queen of Sheba: “I am not a woman: I am a world!”

Second, Nezami is a moralist: He likes to give advice on how we should live. “Khosrow & Shirin” is packed with gnomic sayings, most often urging us to shun this mutable world, practice self-control and aspire to a more spiritual way of life. At times, one can even read the poem as an allegory of, and invitation to practice, a kind of Sufi mysticism:

Seek peace, then nothingness, and you will leave

This earth’s existence, where you’re forced to grieve —

Let the wind take your soul, forsake here, sever

Your ties to earth’s foul prison-house forever.

The world’s contemptible, and will desert you.

Third, and most interesting of all, Nezami’s hero and heroine aren’t at all the earthly paragons they’re said to be. King Khosrow is sybaritic, deceitful, boastful and often drunk, while Shirin doesn’t seem to know her own mind. When we first meet this niece of the ruler of Arman, she’s a bit spoiled and used to getting her way. Though she weeps and pines for Khosrow, and regularly seems ready to succumb to his imploring advances and his call to “seize the day,” a sense — a shrewd sense — of her own worth inevitably reasserts itself, and she sends him packing. Here’s Khosrow sounding a typical plea:

Come through this doorway into happiness

Where life consists of pleasure and success,

And let us live tonight, since who can know

What turns of Fate tomorrow’s dawn will show?

The king usually then adds how much he utterly adores Shirin, but she wisely puts no trust in his words:

But no, you simply want to have me handy

To sweet-talk when you’re drunk, to crunch like candy,

To get me careless drunk and have your fun,

Share this articleNo subscription required to readShare

A rose to sniff, and throw out when you’re done!

When the two first meet, Shirin appears more tough-minded than she really is, telling the youthful Khosrow, then living in exile, that “only when you’re crowned will you obtain/ The sought-for prize that you’re so keen to gain.” She insists on marriage, on becoming queen — not just another concubine. But when Khosrow does regain his kingdom, largely through the help of the emperor in Byzantium, he is required to wed that sovereign’s devout daughter Maryam, who, Nezami slyly adds, “made a Christian heaven of his life.” Not surprisingly, Khosrow is again soon yearning for Shirin.

She, in her turn, is suffering sleepless nights over him when not ravaged by jealousy:

What is my heart that I should care for it?

I’ve had no joy of it, no benefit.

At times Fate hurts us all, but I’ve no way

To halt this pain that’s here day after day;

Oh, I was happy once, but then I fell

From blissful days to days of endless hell.

How long must I hide all this ceaseless burning!

When shall I see the end of all this yearning?

Halfway through this long poem, Nezami introduces a stonemason, a gentle giant named Farhad, who grows so dazzled by Shirin that he wanders into the desert, forgets to eat and thinks of nothing but his adored and unattainable beloved. Medieval knights tended to behave this way too, for courtly love easily morphs into religious mysticism.

Compared with Farhad’s pure devotion, Khosrow keeps on living for pleasure, and once he hears about an apparently promiscuous beauty named Shekar, he can’t get her out of his mind. What follows is one of the most entertaining sections of the poem, an example of that universal folklore motif, the bed trick. After Shekar entertains Khosrow, she sends a maid, dressed to resemble her mistress, to spend the night with the blind-drunk king. In the morning, Shekar innocently settles beside the smug Khosrow, who asks if she’s ever encountered any lover as virile as he is:

She said, “Oh, you’re the best, I swear it’s true,

I’ve never seen another man like you!”

But then she adds the kicker:

T

here is one tiny fault we might regret —

Your breath smells dreadful; please don’t be upset!

As the poem progresses, Nezami sets up multiple situations in which the two lovers argue about their feelings for each other. When an intoxicated Khosrow tries to make his way into Shirin’s castle, she staunchly keeps the gates locked and guarded, even though it’s snowing. Nonetheless, when the time is finally right, Shirin overcomes her pride and sexual reticence, so that she can murmur to her beloved: “Make me the wine you drink tonight.”

As for Khosrow himself, he gradually comes to realize that “I’ve spent my days/ Searching for useless things in useless ways!” Through Shirin’s civilizing love, the self-indulgent king slowly progresses from a pointless life to a spiritually meaningful and selfless one. In the end, not even death will separate Khosrow and Shirin.

By Michael Dirda

Michael Dirda is a Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist for The Washington Post Book World and the author of the memoir “An Open Book” and of four collections of essays: “Readings,” “Bound to Please,” “Book by Book” and “Classics for Pleasure.”