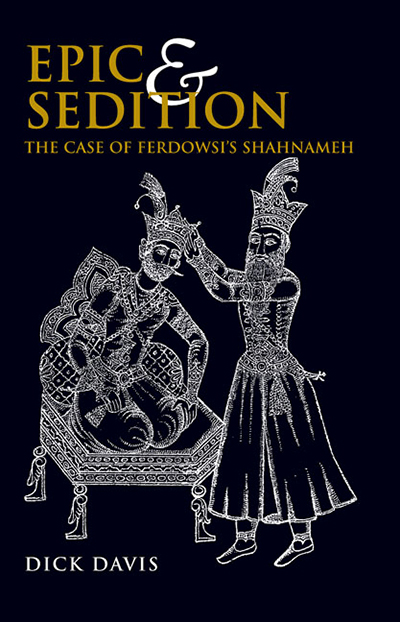

THE SHAHNAMEH (Book of Kings) is the national epic of Iran composed by the poet Ferdowsi between 980 and 1010 AD. It tells the story of ancient Persia, beginning in the mythic time of Creation and continuing forward to the Arab-Islamic invasion in the seventh century. Brilliantly translated into prose and verse (in the naqqali tradition) by the poet and Ferdowsi scholar Dick Davis and magnificently illustrated with miniatures from the greatest Shahnameh manuscripts of the 14th to 17th centuries (in museums and private collections around the world), these volumes give English-language readers access to a world of vanished wonders.

THE LION AND THE THRONE, volume I of this series of the major stories of the Shahnameh, covers the first third of the poem and broaches the themes of Ferdowsi’s epic: the origins of civilization; the notion of kingship; tenderness and a longing for justice and social order. The stories in this volume include: The First Kings; The Demon-King Zahhak; Feraydun & His Three Sons; The Story of Iraj; The Vengeance of Manuchehr; Sam & the Simorgh; Zal & Rudabeh; Rostam, the Son of Zal-Dastan; Iran & Turan; Rostam & His Horse, Rakhsh; Rostam & Kay Qobad; Kay Qobad & Afrasyab; Kay Kavus; War Against the Demons of Mazandaran; The Seven Trials of Rostam; The King of Hamaveran & His Daughter Sudabeh; The Tragic Tale of Sohrab. There are also a glossary of names and their pronunciation, a summary of the complete Shahnameh, and a guide to the Persian miniatures which illuminate the tales.

FATHERS AND SONS, volume II of the series, opens and closes with tales of tragic conflict between a king and his son: Prince Seyavash and Prince Esfandyar are both driven from the court by their foolish fathers to confront destiny and death in distant lands. Interwoven with Seyavash’s story is the tale of his stepmother Sudabeh’s lust for her young stepson, and of his escape from her tricks by the famous trial by fire; Esfandyar’s story involves the last combat of the great Rostam, a fight to the death which leads to Rostam’s own demise at the hands of his evil brother Shaghad. Between these two stories the reader travels through a wondrous landscape of romance (Bizhan and Manizheh), demons (the Akvan Div), heroic despair (the tale of Forud) and mystical renunciation of the world (Kay Khosrow’s mysterious last journey).

SUNSET OF EMPIRE, the third and final volume of the series, moves from mythology and legend to romanticized history. Here the mighty events that shook ancient Persia from the time of Alexander of Macedon’s conquest to the Arab invasion of the seventh century are reflected in the stirring and poignant narratives of Ferdowsi, the master poet who took on himself the task of preserving his country’s great pre-Islamic heritage. Vast empires rise and fall, the rule of noble kings and cruel tyrants, the fortunes of a people buffeted by contending tides of history. Larger than life individuals are vividly depicted—the impulsive, pleasure-loving king Bahram Gur, the wise, long-suffering vizier Bozorjmehr, the brave rebel Bahram Chubineh, his loyal defiant sister Gordyeh, and many others—but we also see many vignettes of everyday life in the villages and towns of ancient Persia, and in this part of the Shahnameh Ferdowsi indulges his talent for sly humor much more than in the earlier tales. The poem rises to its magnificent climax in its last pages, when the tragic end of an era is recorded, and Ferdowsi and his characters look with foreboding towards an unstable and fearful future.

The Story of Kebrui;

Bahram Forbids the Drinking of Wine

At dawn the next morning Bahram called for wine, and his courtiers began another round of merry-making. At that moment the headman of a village entered with a present of fruit: he brought camel-loads of pomegranates, apples and quinces, and also bouquets of flowers fit for the royal presence. The king welcomed this man, who had the ancient, noble name of Kebrui, and motioned him to a place among the young men there. He handed him a large goblet of wine, that held two maund. The visitor was pleased at the king’s and his courtiers’ attention, and when he had drained the cup, he caught sight of another and felt a craving for it in his heart. In front of all the nobles there he reached out and seized it. He stood and toasted the king, and said, “I’m a wine-drinker, and Kebrui is my name. This goblet holds five maund of wine, and I’m going to drain it seven times in front of this assembly. Then I’ll go back to my village, and no one will hear any drunken shouts from me.” And to the astonishment of the other drinkers there he drained the huge cup seven times.

With the king’s permission he left the court, to see how the wine would work in him. As he started back on his journey across the plain, the wine began to take effect. He urged his horse forward, leaving the crowd who were accompanying him behind, and rode to the foothills of a mountain. He dismounted in a sheltered place and went to sleep in the mountain’s shadow. A black raven flew down from the mountain and pecked out his eyes as he slept. The group that had been following along behind found him lying dead at the foot of the mountain, with his eyes pecked away and his horse standing nearby at the roadside. His servants, who were part of the group, began wailing and cursed the assembly and the wine.

When Bahram awoke from sleep, one of his companions came to him and said, “Kebrui’s bright eyes were pecked out by a raven while he was drunk at the foot of a mountain.” The king’s face turned pale, and he grieved for Kebrui’s fate. Immediately he sent a herald to the palace door to announce: “My lords, all who have glory and intelligence! Wine is forbidden to everyone throughout the world, both noblemen and commoners alike.”

The Story of the Cobbler’s Son and the Lion:

Wine Is Declared Permissible

A year passed, and wine remained forbidden. No wine was drunk when Bahram assembled his court, or when he asked for readings from the books that told of ancient times. And so it was, until a shoemaker’s son married a rich, wellborn, and respectable woman. But the shoemaker’s boy’s awl was not hard enough for its task, and his mother wept bitterly. She had a little wine hidden away; she brought her son back to her house and said to him,

- “Drink seven glasses of this wine, and when

- You feel you’re ready, go to her again:

- You’ll break her seal once you two are alone—

- A pickax made of felt can’t split a stone.”

The boy drank seven glasses down, and then an eighth, and the fire of passion flared up in him immediately. The glasses made him bold, and he went home and was able to open the recalcitrant door; then he went back to his parents’ house well pleased with himself. It happened that a lion had escaped from the king’s lion-house and was wandering in the roads. The cobbler’s son was so drunk that he couldn’t distinguish one thing properly from another; he ran out and sat himself on the roaring lion’s back, and hung on by grasping hold of the animal’s ears. The lion keeper came running with a chain in one hand and a lariat in the other and saw the cobbler’s son sitting on the lion as unconcernedly as if he were astride a donkey. He ran to the court and told the king what he had seen, which was a sight no one had ever heard of before. The king was astonished and summoned his advisors. He said to them, “Inquire as to what kind of a man this cobbler is.” While they were talking, the boy’s mother ran in and told the king what had happened.

- She said to him, “May you live happily

- As long as time endures, your majesty!

- This boy of mine’s just starting out on life—

- He’d found himself a satisfactory wife.

- But when the time came . . . well, his implement

- Was just too soft, and he was impotent.

- So then I gave the boy (but privately,

- To make him father of a family)

- Three glasses of good wine; at once his face

- Shone with a splendid ruby’s radiant grace,

- The floppy felt stirred, lifted up its head,

- And turned into a strong, hard bone instead.

- Three drafts of wine gave him his strength and glory

- Who would have thought the king would hear the story?”

The king laughed at the old woman’s words and said, “This story is not one to hide!” He turned to his chief priest and said, “From now on wine is allowed again. When a man drinks he must choose to drink enough so that he can sit astride a lion without the lion trampling him, but not so much that when he leaves the king’s presence a raven will peck his eyes out.” Immediately a herald announced at the palace door, “My lords who wear belts made of gold! A man may drink wine as long as he looks to how the matter will end and is aware of his own capacity. When wine leads you to pleasure, see that it does not leave your body weak and incapable.”